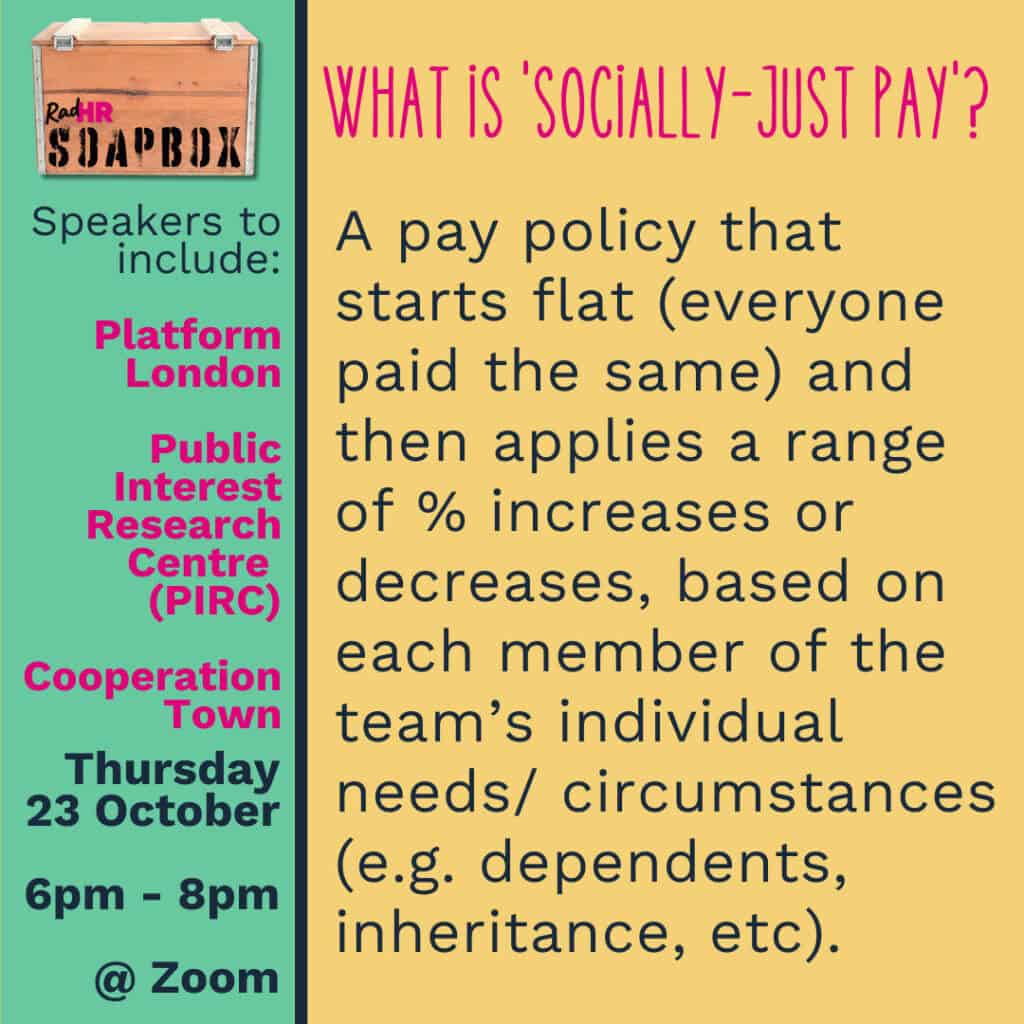

A growing number of organisations are exploring what more equitable approaches to pay can look like. On 23 October, RadHR convened the 2nd Soapbox event, bringing together groups who have been experimenting with socially-just pay policies to talk about why they have adopted them, how they are implementing them, and what they have learned through the process.

Pay is one of the most concrete ways, within our groups and organisations, that we can begin to address the inequalities of the wider world. Paying one another according to our actual needs and circumstances is a radical act that can begin to counter some of the many ways wider systems of oppression impact on people’s lives. (If you’re new to more-equitable pay models, and want a simple outline of what ‘socially-just pay’ means, check out this short video we made).

That said, even a well-resourced organisation will never have the power to address all the endless impacts of the capitalist white supremacist cis-heteropatriarchy. But paying those who are at the sharper end of those systems, in a way that recognises the many more-and-less direct financial costs associated with oppression – and economic inequality, more generally – can be a powerful start.

While socially-just pay policies certainly have their challenges, it’s important that these are seen in the context of the many shortcomings of standard hierarchical (and supposedly meritocratic) pay structures that most organisations adopt without a second thought. These include: the inequalities they breed amongst workers, the low wages they foster (to subsidise senior salaries), and their tendency to reinforce economic benefit to those who already have it (better paid jobs going disproportionately to those who have had more social, economic and educational opportunities).

Equitable pay also addresses one of the core shortcomings of flat/equal pay. Many of the organisations who have ended up adopting more-equitable waging, have moved on from a flat pay structure when they begin losing staff because their life circumstances changed. Unless an organisation can pay everyone far more than they all need to live, when people’s costs change, they can easily be ‘priced-out’ of a role that used to be financially viable for them. In any case, in many flat pay organisations, a low flat pay rate has already precluded a lot of people from even applying to work with them, if it’s not offering them enough to get by on.

So while more-equitable pay is far from perfect, it still takes steps to challenge organisational complicity in wider social inequalities. RadHR came together with Platform London and Cooperation Town in October, to explore our shared belief that equity involves questioning a lot of the fundamental assumptions about how we think about and distribute wages in our organisations. (We hoped to have Public Interest Research Centre (PIRC) in the conversation as well, but illness struck and left us down one panelist.) This blog captures some of the themes of the conversations we had, and adds a bit more detail about a still-little-known organisational pay practice, which offers important insights for organisations wanting to think about what equity means in their day-to-day operations.

What other policies do you need to think about?

For a socially-just pay structure to work best, it needs to be seen in the wider organisational policy context: is pay always the best way to address different people’s life circumstances? Money can be a useful proxy for a lot of issues people face (higher food bills, transport or care costs, etc.), but not all. Could additional paid time off, or a staff counselling subsidy, or a generous expenses policy, more directly get to someone’s needs?

Being able to see how a pay policy fits with a wider range of staff support systems will always be critical. Policies made in isolation will often miss opportunities or try to do more than they are designed to do. Having a clear sense of what a socially-just pay policy can and can’t do for your particular group’s context, goes a long way towards making it more effective in addressing different people’s needs.

Money and conflict

As positive as equity in pay sounds, it’s not without its challenges. As relationship therapist Esther Perel, and her collaborator, Mary Alice Miller write, ‘Money is never just about money’:

“Money is about status, access, comfort, freedom, interdependence, trust, loyalty, betrayal, fairness, and more. Money is tied to our sense of self-worth and our feelings of power and powerlessness. Financial success is often interpreted as proof that we’re ‘doing something’, and even more so, that we’re ‘worth something’. Whereas financial failure can feel like we’ve failed at life itself and that we’ll never get out of the hole.”

They write these words in the context of intimate relationships, but would any of these connotations be less-true when we talk about wages from our work? If conversations about household budgeting, career progression and personal spending can be among the most common sources of conflict in a couple, why would we think that in a workplace – where we rarely have the same level of trust in our colleagues – these conversations would be smoother?

Maybe this reality accounts for the very slow uptake of more equitable models of organisational pay, even as countless groups and collectives move towards understanding the importance of embedding equity in our collective structures? Maybe the simplicity of existing pay structures – for all their inherent inequities – saves us having to go to some tricky places, individually and collectively?

At a basic level, socially-just pay means a level of honest collective discussion about what we each need to live decent lives, in the trashfire of late-stage capitalism. Whether you grew up rich, poor, or experienced either of those things at any point along the way, you probably have some sensitive spots when it comes to money. And these sensitive spots can grow exponentially when they rub up against each other.

But as with many things, the tensions don’t always last. Often the anticipation of the conversation is harder than the actual conversation itself. It may be that the vulnerability that comes from sharing your financial needs and circumstances with one another, actually offers an opportunity to learn about and grow closeness with the people we work and organise with every day. As my colleague Rich said, “I know that I have a lot more empathy, a sense of the major things that affect people’s lives [through socially-just pay discussions], and I have that front-and-centre in ways that affect other parts of my work… The conversations you are having are building a stronger team.”

Is flat pay a necessary stepping stone to equitable pay?

It’s also important to hold in mind that the wider social narratives around pay are still a long way from centring equity. The default assumption that some people’s time is inherently worth more than others – whether due to seniority, education, expertise or other measures – still has a lot of traction, even in many progressive circles.

Hierarchy is still the norm.

Amongst the orgs that those of us at the event were part of (or were aware of practicing versions of socially-just pay), all had either made the choice for pay equity from day one, or had transitioned to equitable pay from flat pay. In the latter case, this transition was often the result of being forced to see the ways in which ‘flat’ pay perpetuated certain inequalities, due to the difference in people’s living costs.

None of us had heard of a group transitioning directly from a traditional pay hierarchy, to a socially-just model. We could only speculate, but perhaps it feels too difficult for those who have been in senior leadership roles to let go of their economic positions, potentially becoming less-well remunerated than colleagues who they have been more senior to. But as we hadn’t been in or heard of these positions, all we could do was guess!

Disability and other areas we need to better understand

Given what a small sample size we were as organisations, it was very clear between us that the dozens of workers who had been through these pay policies in all of our organisations, were not reflective of all the workers who these policies could benefit. Disability and pay was a particular area that each of us pointed to needing to learn more deeply around, given the many varied experiences of disability. We also spoke about the importance of balancing the ways in which a progressive pay policy needs to be complimented by radical approaches to time off and differing expectations of work, which don’t perpetuate default hyper-productive norms.

“We won’t have everything, we will never cover every possible area,” Shiri from Cooperation Town commented. “But where does disability intersect with class, with parenting, with housing… what does it mean? How does it impact all those other areas?”

Transparency vs. privacy

One tension at the Soapbox event was if it is more important to create a transparent process (where everyone is clear on what everyone else is making, and why) or if individual privacy (given the traumatic relationships many of us have to money) is more appropriate?

Between us, we found we had come to place different emphases on each of these positions in our organisational pay processes. On the one hand, Cooperation Town have full team meetings where everyone is encouraged to state explicitly which pay adjustments would apply to them; on the other hand, at RadHR, we let each worker decide for themselves which uplifts and downlifts are relevant, do the maths and come back with an overall percentage shift on the baseline pay rate.

We all agreed that trying to police one another’s decisions was not aligned with our values, however public or private the process of administering the policy was. What level of openness we expected to have with each other was quite varied though. There was a sense that transparency was the ideal, but whether it could be more meaningfully achieved through a fully-open process, or by building gradual trust by letting everyone have the privacy they want (and then becoming more open in future conversations, as it felt possible) was still a question.

Give yourselves enough time together

Something we all agreed on was the importance of making the time for conversations to go well. Even for those where there had been less tension amongst a group, there was a shared sense of importance around making the space to go deeper with the questions that this approach to pay would raise.

“None of the time has been wasted”, Tanya from Platform London said. “It’s been a really good way of very tangibly talking… about our anti-oppression strategy… we haven’t just had those conversations in theory. None of it is wasted work, even though it can seem time-consuming.”

Socially-just pay resources

3min Instagram intro video to socially-just pay

Article introducing different needs-based pay models (including socially-just pay).

Meeting template for discussing and agreeing details of a socially-just pay policy with your team (including asocially-just pay calculator for figuring out the costs of different adjustments, across different workers).

Socially-just pay policies from the RadHR library:

Adfree Cities Pay Policy

Original Platform London Socially Just Waging System

PIRC Socially Just Pay

RadHR Pay Policy

Cooperation Town Socially Just Waging System

Tripod Equitable Wage Policy

Comment on our forum: community.radhr.org